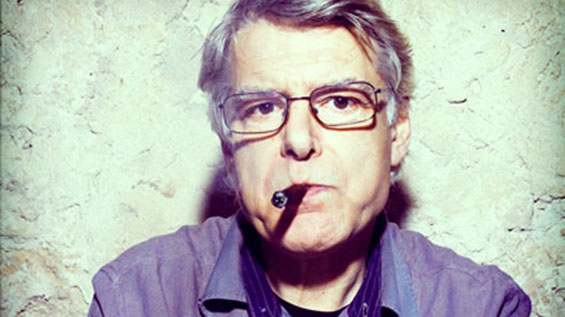

Thanks to the support of the Columbia University Italian Academy for Advanced Studies in America, the British music critic, novelist, and librettist Paul Griffiths has written a specially commissioned long-form program note for February 21st’s concert, featuring Luigi Nono’s 1989 masterpiece La Lontananza Nostalgica Utopica Futura. We invite you to read it in advance of the concert, or join us at 7 p.m. to read a print version that will be available on-hand before the 7:30 p.m. performance.

Thanks to the support of the Columbia University Italian Academy for Advanced Studies in America, the British music critic, novelist, and librettist Paul Griffiths has written a specially commissioned long-form program note for February 21st’s concert, featuring Luigi Nono’s 1989 masterpiece La Lontananza Nostalgica Utopica Futura. We invite you to read it in advance of the concert, or join us at 7 p.m. to read a print version that will be available on-hand before the 7:30 p.m. performance.

§

A lone figure, violin and bow in hand, enters and walks across the stage toward a music stand, where this figure, musician, stops and begins to play. The notes may be abrupt, frenetically maintained, or quiet and long; they may come singly or in singing lines, may be assertively present or faintly redolent of former times. Whatever their nature, their character is one of search, because there is always this urge, within the continuity they create, to begin again. They search out the space into which they spill. They search, perhaps, for the impossible, for an exit from that space.

That space is already occupied – has been occupied from before the musician entered – by swarms, clouds, jets of pre-recorded sounds, many of them still evidencing their source in the same instrument, the violin. One might imagine an orchestra of violins in searing intensity, or a choir of voices that are reconstructed violins, or a group of violins tuning, or an industrial noise that still has within it the abrasive edge of hair on string.

The work being performed is La lontananza nostalgica utopica futura, composed in 1988 by Luigi Nono and revised the following year. Title, date and composer are all very relevant to what is going on here.

First, the title – “The Distance, Nostalgic Utopian Future,” one might say, keeping the Italian word order, or “The Nostalgic Utopian Future Distance.” We are being invited to listen to a distance that is a distance in time, a distance we simultaneously listen across, to something at the further end of that distance, and listen into, the distance itself the object of our scrutiny. It is a distance in the past (hence the nostalgia) and also in the future, which it can be because it is the distance to a dream, a dream of a Utopian future that has, with the passing of time, not come closer but rather receded.

Twenty years had gone by since the heady days of 1968, when it seemed that a noisy but peaceful and positive revolution was about to overtake the western world. To some extent, the hope had been fulfilled. A disastrous war had been brought to an end and not (so far) replicated. Constraints based on race, sex, and sexuality had been removed. And yet the heads of government – Ronald Reagan, Margaret Thatcher – did not look or behave like proponents of radical change. Rather the reverse. The status quo had been patched up, ready to go on.

As for the composer, Luigi Nono, born in Venice in 1924, had grown up under Mussolini’s fascism and spent his late teenage years experiencing war. When that war ended, he was, like many of his generation, determined there should never be another. Responsibility for the war lay with the fascists. There had to be a wholly alternative polity, and Marxist communism, proposing equality of opportunity, participation, responsibility, and reward, seemed like the one.

Nono joined the Italian Communist Party in 1952, and his works gained a social-political edge; his first opera, Intolleranza 1960, concerns the hostility a migrant worker faces on every side. However, Nono’s vigorous adherence to an avantgarde language, post-Schoenberg, post-Varèse, gained him few friends in eastern Europe, while his insistence on messages of fierce political engagement lost him those he had among western European composers of his generation, such as Pierre Boulez and Karlheinz Stockhausen.

Support from outstanding performers – notably Claudio Abbado and Maurizio Pollini, for whom he wrote his piano concerto Como una ola de fuerza y luz (1971-2) – must have helped, but there was irony here, too, since by this time he was distancing himself from normal concert life, preferring presentations in factories. He had composed a work specifically for such occasions, La fabbrica illuminata (1964), for soprano and tape. Increasingly alone, and probably feeling that to be inevitable, he began writing more interior music, notably his string quartet Fragmente–Stille (1979-80), which was his first work since the early 1960s with no electronic component.

Much of his work of the next several years revolved around Prometeo, a non-opera for solo voices and instruments, chorus, and orchestra, with live electronic transformation, a “tragedy of listening”, as he called it, that was also a treatise in listening, demanding close concentration on individual sonorities. Before we could listen to music again, we had to learn to listen to sounds, learn to navigate ourselves in aural environments lacking all the conventional gravitational forces and compass bearings.

Following the first performance of Prometeo, in Venice in 1984, Nono produced several live-electronic pieces for performers drawn to him by his music’s uncompromising difference and insistence: the flutist Roberto Fabbriciani, clarinetist Ciro Scarponi, vocalist Susanne Otto, and tuba player Giancarlo Schiaffini. During this period he also found a mantra in words inscribed on a wall in Toledo: “Caminante, no hay caminos, hay que caminar” (Wanderer, there are no ways, only the wandering), adapted from a poem by Antonio Machado. This line is variously contemplated in four of his last works, two for large forces and two for small, these being La lontananza nostalgica utopica futura and its successor for two violins, «Hay que caminar» sognando.

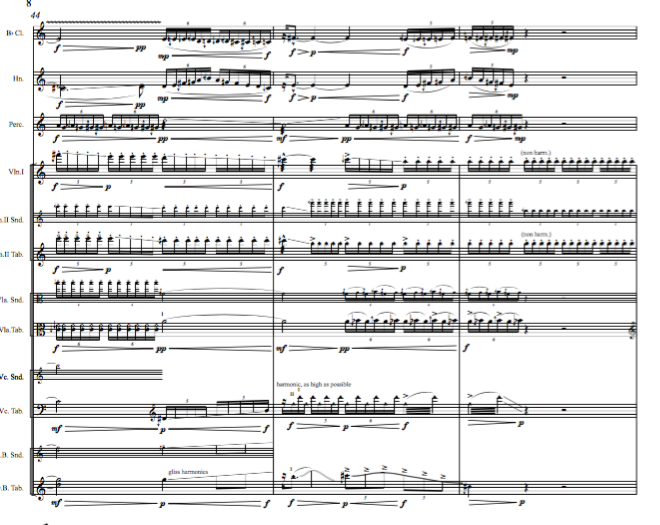

Hence, in part, the former work’s subtitle: “Madrigale a più ‘Caminantes’ con Gidon Kremer”, the “more wanderers” here being the eight electronic tracks on the tape that is playing alongside the violinist. These tracks, in pairs, convey different kinds of material, which the composer’s assistant André Richard describes as follows:

“Tracks 1-2: Very dense, variously overlaid harmonic material,

“Tracks 3-4: Original [violin] sounds of various playing techniques, single tones, and fifths,

“Tracks 5-6: Voices, words, noises of doors, chairs, etc., also violin sounds [all recorded during the recording process],

“Tracks 7-8: High melodic material, melodies in harmonics, fast tremolos, with the bow leaping or thrown off the strings.”

The tape – or, nowadays, a digitalized copy – plays for sixty-one minutes, which is therefore the maximum length of a performance. Its operator is free to cut or fade tracks in and out, in momentary response to the violinist’s playing or with regard to some larger concept of form. This person must therefore be almost as supple and sensitive as the violinist – and as acute a listener.

Nono in his subtitle places the electronic “wanderers” first not in order to diminish the soloist – whom, indeed, he names, and whose sound will be forever part of the piece, integral to the tape parts – but rather to underline how the work “is not in any circumstances a concerto for solo and accompaniment,” to quote his instructions from the score. The electronic tracks trace out paths the violin will not – cannot – take, but they engender, too, the environment within and around which it will – must – orient itself. And this is a madrigal because, like those of the Renaissance, it is a polyphonic composition.

The composer himself operated the tape at the first two performances, given in Berlin on September 3, 1988, and in Milan four weeks later; according to Richard, the result was different each time. By the time Kremer and the tape tracks came together again, to make the first recording, for Deutsche Grammophon, in December 1990, the composer had departed this world.

For those two earliest performances, Nono wrote a program note in short paragraphs, spaced out on the page in short lines, to reflect how the violinist’s several music stands are spaced out on the stage, and also potentially in the auditorium. The violin part is divided into six segments, each of which has its own stand, with two, three, or four empty stands also present, so that the musician is faced with many possible routes and with the possibility of (seeming) error. Nono’s note is given below, in italic type.

The nostalgic-utopian distance

is friend to me and despairing

in continuous restlessness.

The crucial word “distance” Nono took from the title of Salvatore Sciarrino’s solo flute piece All’aura in una lontananza. (Sciarrino was to supervise the electronic sound for a fascinating recording, on the Kairos label, that takes the music a little towards his own whispered world while using the full length of the tape.) But Nono, of course, made the word his own, relating it not merely to his political hopes but also to his sense of a widespread alienation from a world in cultural decay, of people living in distance from each other, and from themselves.

The rare qualities of the sounds

invented by Gidon bring about

a sounding in the various spaces

of the Kleine Philharmonie.

The small hall of the Philharmonie in Berlin was the site of the première. Seeking to challenge the hegemony of composers over performers, Nono was eager to involve musicians close to him in creating a work.

How the articulated spaces,

of the Kleine Philharmonie

offer other spaces for

Gidon’s original sounds:

far – near –

meetings – clashes – silences –

internal – external –

overlapping confusions.

Again, there is this concern with sound in space, with sounding space, this time, presumably, with regard to the live violin. Nono was a Venetian, and lived his whole life in Venice. He was familiar with the sounds of sloshing water, of voices, of boat engines, of birds, echoing through the city from unseen sources, and he was familiar, too, with the music written for St. Mark’s Basilica by Giovanni Gabrieli and Claudio Monteverdi, music for diverse groups of singers and instrumentalists separated from one another, calling out and coming together from within the building’s many connected parts.

Magnetic tapes as voices

of madrigals joining together

solo violin and live electronics –

so many voices –

«CAMINANTES» – «WANDERERS».

It is the idea of the subtitle: a madrigal of wanderers, of voices live and electronic. Obviously the violinist, alone on stage, achieving virtuoso feats, physically pacing out the wandering, will claim a different kind of attention from that given the invisible electronic sounds. Like the voices of a madrigal, however, they make sense only when they come together. Nono did not want the violin part to be performed alone. The only time that happened seems to have been shortly after the composer’s death, when Gidon Kremer gave a solo performance that would speak of absence.

No processing or transformation:

the sounds Gidon makes are original.

Three days devoted to recording at the

SWF Experimental Studio in Freiburg.

This Southwest German Radio (Sudwestfunk) location, in the Black Forest, was where Nono had been working on almost all his electronic endeavors for almost a decade, since 1979, building a close working relationship with the sound engineer Hans-Peter Haller. Nono’s assertion that the violin sounds are unmodified probably refers to the primary version made in the summer of 1988. This is not true of the revised version, for which Richard tells us the composer used harmonizers (transposing sounds), reverberation, filters, delay, and Haller’s own “halaphone,” with which sounds could moved in space.

Infinite listenings – attempts

at choices by way of elective affinities –

various compositional feelings

voice by voice.

The composer is principally a listener, the composition being principally an invitation to listen. It is, moreover, principally by listening – listening to how the electronic tracks will combine, with each other and with the violin, listening to how and where the several wanderers will go – that the composition is made.

like the old Flemings in their imaginings.

Nono refers once more to Renaissance polyphony, an art to which Flemish composers contributed mightily in the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries. In Fragmente-Stille he had quoted from “Malheur me bat,” a three-part song attributed variously to Johannes Ockeghem and Johannes Martini, both of them born in what is now Belgian territory. He may also have been thinking here of a later Fleming, Adrian Willaert, who spent the second half of his life as chief musician at St. Mark’s.

And Gidon abandons himself

to the various spaces with the other

writing-invention.

The violin sound must be directed to the space, and to the other sounds wandering there. This is the most selfless of solo performances.

And abandons them.

A lone figure, violin and bow in hand, leaves the stage to the sounds that for a while go on searching.

Please join us in welcoming Adrian Morejon, Talea’s Interim Executive Director! Adrian assumed the new role in December 2021 and has been a member of the Talea Ensemble as a performer since 2011. Adrian is an accomplished bassoonist and administrator and brings his depth of experiences from both on and beyond the stage to his leadership role at Talea.

Please join us in welcoming Adrian Morejon, Talea’s Interim Executive Director! Adrian assumed the new role in December 2021 and has been a member of the Talea Ensemble as a performer since 2011. Adrian is an accomplished bassoonist and administrator and brings his depth of experiences from both on and beyond the stage to his leadership role at Talea.

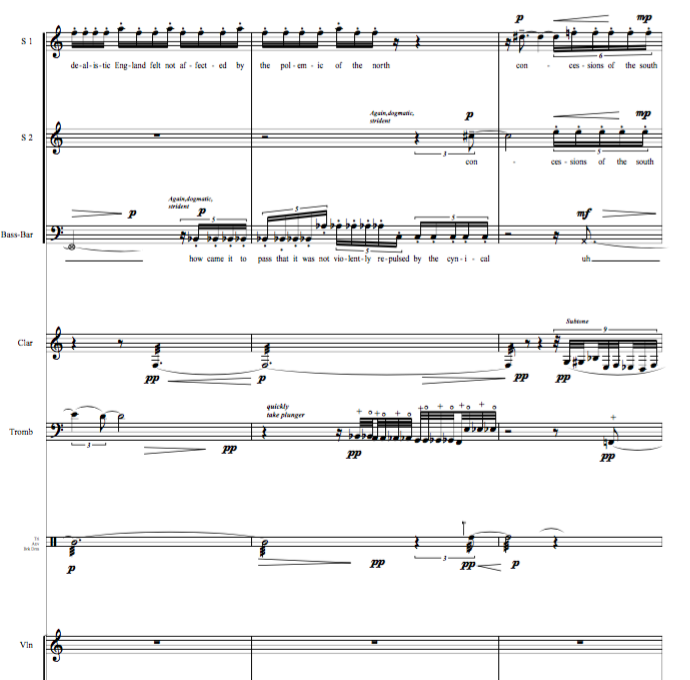

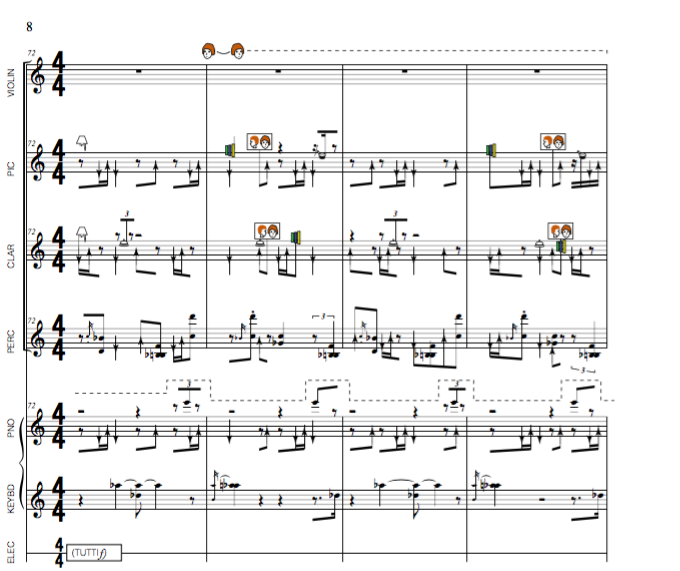

ZS: So, turning to your music, I’m wondering if you can talk about something that I find really vivid about it, which is this combination of very technically engaged virtuosic playing with all these homemade instruments. I think it gives your music this very distinctive and almost “quirky” vocabulary, but everyone walks away from it feeling like everything sounds really good. Everyone feels it draws on all of their skills but also provides a really distinctive musical language for them to play with. How did you refine that and develop it?

ZS: So, turning to your music, I’m wondering if you can talk about something that I find really vivid about it, which is this combination of very technically engaged virtuosic playing with all these homemade instruments. I think it gives your music this very distinctive and almost “quirky” vocabulary, but everyone walks away from it feeling like everything sounds really good. Everyone feels it draws on all of their skills but also provides a really distinctive musical language for them to play with. How did you refine that and develop it? OB: You know, it’s a lot of things. There are different types of rhythm. One thing that’s really important is I always think about downbeats. They hold things together, phrases and downbeats. There’s a starting point and then things move on from that. And, how long is it going to be until the next downbeat? When that beat becomes predictable, how predictable do I want it to be? And is it more interesting (I kind of think it is) for it to be predictable, but with a certain element of unpredictability? It’s not that square, but you still kind of know…

OB: You know, it’s a lot of things. There are different types of rhythm. One thing that’s really important is I always think about downbeats. They hold things together, phrases and downbeats. There’s a starting point and then things move on from that. And, how long is it going to be until the next downbeat? When that beat becomes predictable, how predictable do I want it to be? And is it more interesting (I kind of think it is) for it to be predictable, but with a certain element of unpredictability? It’s not that square, but you still kind of know… Talea premiered Scenes 2-5 of Maxwell Dulaney’s “Already Root” in April 2018, after working in-person in residence in New Orleans. We brought the show back to New York to close our mainstage season on April 13 at St. Peter’s, alongside works by Courtney Bryan, Anna Walton, and Rebecca Saunders. Read on to learn more about Max’s current and upcoming projects…

Talea premiered Scenes 2-5 of Maxwell Dulaney’s “Already Root” in April 2018, after working in-person in residence in New Orleans. We brought the show back to New York to close our mainstage season on April 13 at St. Peter’s, alongside works by Courtney Bryan, Anna Walton, and Rebecca Saunders. Read on to learn more about Max’s current and upcoming projects…

Finally, as with most new composer dads, I am super into the beautifully curious, exploratory babbling and vocal experimentation of my son, Felix. I have been recording him since he was born and am working on a few ways to incorporate him into material for pieces and probably compose an electronics piece out of the recordings.

Finally, as with most new composer dads, I am super into the beautifully curious, exploratory babbling and vocal experimentation of my son, Felix. I have been recording him since he was born and am working on a few ways to incorporate him into material for pieces and probably compose an electronics piece out of the recordings. Courtney’s new work “In the Heart of God” will be performed tonight on Talea’s

Courtney’s new work “In the Heart of God” will be performed tonight on Talea’s

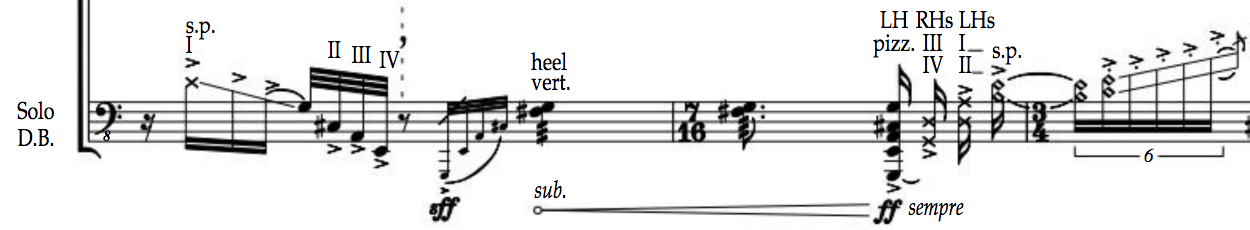

Talea’s illustrious bassist, Greg Chudzik, is the featured soloist in Rebecca Saunders’ “fury ii” in the

Talea’s illustrious bassist, Greg Chudzik, is the featured soloist in Rebecca Saunders’ “fury ii” in the