Greg Chudzik, double bass

Talea’s illustrious bassist, Greg Chudzik, is the featured soloist in Rebecca Saunders’ “fury ii” in the concert this Friday, April 13th, at St. Peter’s Chelsea. We talked about Rebecca Saunders’ music, Greg’s many musical hats, and bonded over freelancing in NYC.

Talea’s illustrious bassist, Greg Chudzik, is the featured soloist in Rebecca Saunders’ “fury ii” in the concert this Friday, April 13th, at St. Peter’s Chelsea. We talked about Rebecca Saunders’ music, Greg’s many musical hats, and bonded over freelancing in NYC.

ZS: So, Greg, how long have you been with Talea and how did you get involved? Do I remember correctly that you met Alex Lipowski at Lucerne?

GC: Yeah, I was at Lucerne in 2008, and Alex was a fellow, too. I had found out from a friend there was an ensemble called Talea back in New York, and they were looking to program a huge work by Fausto Romitelli with a bass part. I found Alex in the percussion section, and told him that I would be interested. After that I kept playing more and more with the group, until I officially became a member in 2013.

ZS: What brought you to New York City, then? You would have just finished at the Eastman School of Music?

GC: I had just finished Eastman. I was thinking of going to graduate school, but also asking myself a much bigger question: “why do I want to go to graduate school?” I didn’t really have a sufficient answer. I moved to New York City because I couldn’t think of anywhere else to live, and I figured I would make it as a musician. Obviously that did not happen as quickly as I thought it would.

ZS: Tell me about it! [laughs]

GC: Yeah. I worked on a cruise ship for two months, playing cabaret music. I saved up enough money to move to New York City, and I figured by the time my $5,000 ran out that I would be a star. Well, that $5,000 went very quickly, and I ended up having a bunch of day jobs. I worked at Bear Stearns for a while, and then in 2008 the economy completely collapsed, and Bear Stearns was no longer.

ZS: What did you do for Bear Stearns?

GC: I worked in HR. I hired a bunch of people, and then I fired a bunch of people when things turned south. At the same time, I started playing a bunch of music—a lot of $50 jazz gigs at restaurants that probably didn’t want jazz in the first place.

ZS: [laughs]

GC: I started playing new music, because it was something that I had been interested in throughout music school, and I found that there was more structure around it than there was in the jazz world—and it was a more open environment.

ZS: Really?

GC: Well, maybe not “open”, but there’s definitely more structure. The fact that it’s more institutionalized is kind of a nice thing.

ZS: So, it’s not something you necessarily did a lot of at Eastman? There’s of course an amazing tradition of new music performance, there.

GC: Well, I suppose I did quite a bit. That’s where I met Brad Lubman, who I still work with a lot. But, at Eastman I started as just a jazz major. I was convinced that I was just going to study jazz, although I took classical lessons as well. But, the jazz department at that time was in an interesting state of flux, where they were trying to get people to play a much more orthodox version of jazz. I think there was previously a tradition that was doing a lot more experimental stuff—which wasn’t necessarily considered “jazz” but still under the realm of improvisation. I was really interested by more of the improvisation stuff. But, at the same time, I realized there was this new music community at Eastman, and I found that was more what I wanted to do as a musician than just playing bebop tunes.

ZS: That brings up an interesting question. We often have these conversations in the music world about audiences and engagement and outreach. As someone who has a foot in both jazz and classical worlds, can you talk a little bit about this? About experimental visions of music-making in the future, versus these kinds of orthodoxies? In classical music I think there’s often this unfortunate idea that jazz is more “popular” and therefore doesn’t address these kinds of questions, but in a lot of ways I feel it’s the opposite: the jazz world thinks about it even more.

GC: Well, I think to tell any jazz musician that jazz is more “popular” than literally any other form of music would be almost laughable, from their perspective.

ZS: Really?

GC: Well, look, we live in New York City, which is considered an epicenter of jazz. But, one of the most amazing concerts I’ve seen was this great jazz guitarist, Ben Monder, who is in my opinion one of the best in the world at what he does. It was at 4 pm on a Sunday in the back room of some bar, and there were about 4 other people there.

So, the jazz audience—and I know this is hard to believe coming from the “modern classical” world—might be even narrower. And, what I notice in the jazz and classical world has less to do with the content of the music itself so much as who is making the music and who is considered in the “in crowd”. You know, I think there’s a lot of reflection going on based on gender and based on race in the modern classical world, and I think it’s finally starting to really affect the kind of music that’s being made. This year’s winter jazz was a really interesting example of this.

Let’s face it: Most music has been made by white males, and more and more is being performed by not white males—and, thankfully, more and more is being written by not white males, too. It still needs to happen more, and the jazz world has a long way to go before it reaches gender parity.

I think there’s a tendency to talk about that as a component that is separate from the music itself and how it sounds, but I think it does affect it. You’re giving space to more people with different perspectives, and I think that’s inherently going to make a different sound.

ZS: Do you feel the same thing happening in the new music world to the same extent? Or do you think it’s happening more quickly or more broadly in the jazz world?

GC: That’s a good question. You know, it almost seems to be happening at the same rate. I will say probably that scenes that are more rooted in orthodoxy, musically, are much more resistant. Whereas, the more “creative” jazz-oriented world is more quickly approaching more gender parity, for sure.

ZS: It’s certainly something we’re thinking about a lot and talking about a lot in next year’s programming. And, we’re soon unveiling this new “Town Hall” series for next year, and we’re working to champion a lot of these questions.

I’m wondering: how do you find it influences you to be a practicing artist in both these different fields?

GC: Well, I don’t want to call it a “school” of composition, but there’s a lot of music where if you were not told—i.e. if there was no context—it would be very difficult to differentiate improvised music and certain complex notated music. And I don’t think that’s a bad thing! I think it’s really important as a performer to be more of an interpreter and understand the texture the composer is going for.

Now, I’m not endorsing “winging” it: I always try to get a piece of music as close to what’s on the page as possible. It’s a bit cliché, but a lot of people in the jazz world will say that improvisation is spontaneous composition.

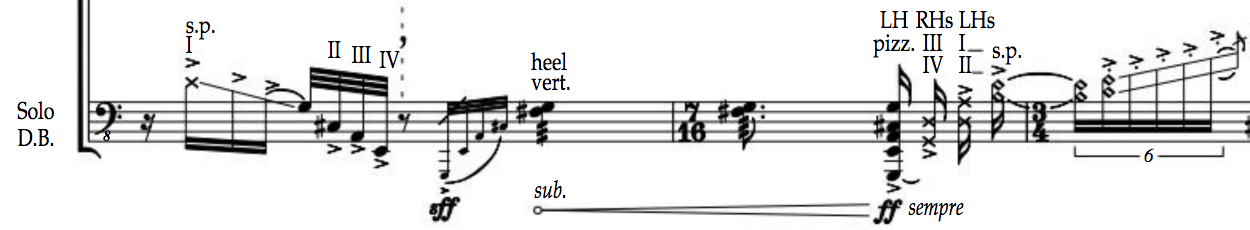

As far as this Rebecca Saunders piece, there’s a lot of information and a lot of very clear information. I really take a lot of time—and pride—in trying to get it as accurately as possible. Just as much, though, I try to take a step back and ask myself: Big picture, what is this going for? What is the sound? I often think: If I were listening to someone improvise, what would be the most important thing? What would stand out?

ZS: Then, what’s the hardest things about the Saunders?

GC: You know, I haven’t rehearsed it with the ensemble yet. It often happens with such a complex piece of music that things I think are going to be hard are actually fine, and vice versa. For me, the biggest challenge in terms of execution is the very specific lexicon of sounds that Rebecca uses in this piece—ones that I think are wonderful. It’s a very limited range of textures, but it’s a very specific range of textures as well. So, you know that whatever she has written, you have to do it very well. I think that’s going to be the difference between an ok performance and a great performance: really honoring those specific textures.

ZS: Yeah, I was going to ask about that, actually. One of the things I personally find hardest about solo playing with an ensemble is the sense of rhythm, pacing, and pulse: always questioning where to compromise and use my chamber music instincts, and where to use a soloist’s instincts and just go, and expect other people to follow me. In this work—where there’s such a mosaic of floating textures until a moment of alignment—how are you preparing?

GC: Yeah, it’s a lot with the metronome. I’m almost coming from the approach of practicing—or, I should say, training—for a marathon. (No one practices for a marathon). Consistency is key: Doing the same thing over and over. When I’m practicing it, I take great pains to make everything as rhythmically accurate as possible. There are definitely some very beautiful, lyrical moments, but, I think you have to cast aside that romantic idea of the “soloist” and focus on just playing as you would in any other chamber ensemble.

The ensemble is not very large, and it’s almost a celebration of the wonderful low frequency textures that the double bass can make. It’s like an inverted solo, where instead of trying to go above the orchestration, you’re going below it. Instead of cutting above the ensemble she’s cutting underneath it.

ZS: Do you have a favorite moment in it?

GC: That’s a great question. I haven’t really played it with the group yet, but I feel like there are going to be some really magical moments that present themselves when I experience the interaction. It’s one thing to listen to the recording, but I think it will be an entirely different experience, first-hand.

ZS: I guess my last question, then, is: as someone who has been freelancing in New York for a decade, I’m sure you’ve seen all kinds of crazy things. This is going on our website, so it has to be safe-for-work, but what’s one of the craziest experiences—musical or otherwise—that you’ve had in your time as a New York freelancer?

GC: One of my most surreal experiences as a musician in NYC has been with my current next-door neighbor in Brooklyn. The variety of methods used to express her displeasure in my practicing is perplexing if not at times terrifying. It started as long letters posted to my door and invitations to official mediation, but quickly escalated. At one point, she left a meticulous log of my practice schedule in the form of message submissions on my webpage. For a while the police would show up at my door whenever she called, but that ended once I got to know the officers (it was always the same officers on the beat, and one of them is a pianist at his church, so he understood). Oddly enough, she hasn’t resorted to playing loud music – only NPR radio. Her current weapon of choice has been singing along loudly (using headphones) with either Alanis Morrisette’s “Jagged Little Pill” or Nirvana’s “In Utero” in album order. Maybe she’ll progress to Meredith Monk at some point!

Tickets on sale now for April 13th, 8 p.m. at St. Peter’s Chelsea (346 W 20th St): Talea plays Bryan, Dulaney, Saunders, Walton. To learn more or purcahse tickets, please visit: https://www.brownpapertickets.com/event/3371233

Greg Chudzik is an active performer across numerous genres on the double bass and electric bass. Currently, he can be seen performing regularly with several new music groups, including Signal Ensemble, Wet Ink Ensemble, and Talea Ensemble. Greg is also a member of several bands, including Empyrean Atlas, Bing and Ruth, and The Briars of North America. He has worked with numerous influential figures in contemporary music, including Steve Coleman, Steve Reich, Pierre Boulez, George Benjamin, Helmut Lachenmann, Charles Wuorinen, Alex Mincek and Tristan Perich. Greg’s recording credits include playing on the Grammy-nominated “Barcelonaza” by Jorge Leiderman, “Morphogenesis” and “Synovial Joints” by Steve Coleman on Pi Recordings, “No Home of the Mind” and “Tomorrow Was the Golden Age” by Bing and Ruth on RVNG records, the album “Americans” by Scott Johnson (Tzadik records), multiple recordings with Signal Ensemble on New Amsterdam and Mode Records, the album “Grown Unknown” by Lia Ices (Secretly Canadian records), the album “Inner Circle” by Empyrean Atlas, and the album “High Violet” by The National on 4AD records. Greg’s debut album “Solo Works, Vol. 1” was released in July of 2015 and features original pieces of music written for bass guitar and electronics.